The 1972 Pontiac Grand Prix, once a vibrant green, has faded to a dusty brown. Abandoned on the slopes of Mount St. Helens in Washington State, the rusty, overgrown wreck stands as a makeshift memorial to Donald and Natalie Parker, a couple of miners killed on May 18, 1980, in one of the most devastating volcanic eruptions in modern history. This is one of the four sites that Olivier Bodart chose as the setting for his novel.

A pyroclastic flow in the Northwest, a landslide in California, and a sinkhole in Florida are all disasters that require the attention of Mat, an investigator for FEMA, the American Federal Emergency Management Agency. But the main character is unable to leave his “center” in Lebanon, Kansas, the geographical center of the contiguous United States. In order to write his reports, he reproduces miniature models of each site in his home – one of the many back-and-forth moments between fictional and personal stories in Olivier Bodart’s novel.

France-Amérique: How did you discover FEMA?

Olivier Bodart: A week before Hurricane Katrina [in August 2005], I was in Louisiana traveling between New Orleans and southern Mississippi in the footsteps of American writer Larry Brown. Shortly after I returned to France, Katrina devastated the region and I discovered FEMA. Everyone was talking about the federal agency at the time, for both the right and the wrong reasons – remember all those people confined to the New Orleans football stadium. After doing some research, I learned that FEMA was originally specialized in water-based incidents before expanding its scope to include all natural disasters. My book focuses on the four elements: water, earth, fire, and air.

Would you say that you are personally fascinated by natural disasters?

There is something terrifying at yet incredibly beautiful about them. I have always been sensitive to the living world and drawn to American geography, its vastness, its weather, its literature, and its stories.

Mat’s character is “paralyzed” by existential angst. You also went through a “period of distress” while writing your novel. Is this a deliberate parallel?

I was about to finish the book when I lost all faith in fiction. I stopped believing in the stories I was reading and those I was trying to write myself. I had been living in the United States for three years when I lost my taste for fiction. I had been hired by the Lycée Français de Chicago to head up the art department and teach visual arts, and arrived with my family in 2012. But the expatriation proved too hard to bear, and my daughter and my now ex-wife went to live in Washington D.C. This is where the distress comes from, a family trauma, a geographical and emotional separation. This is one of the novel’s themes: What is distance? How can we be involved, or not? Mat decides to stay in his center, preferring to recreate reality instead of living it.

Is this where your and Mat’s personal stories diverge?

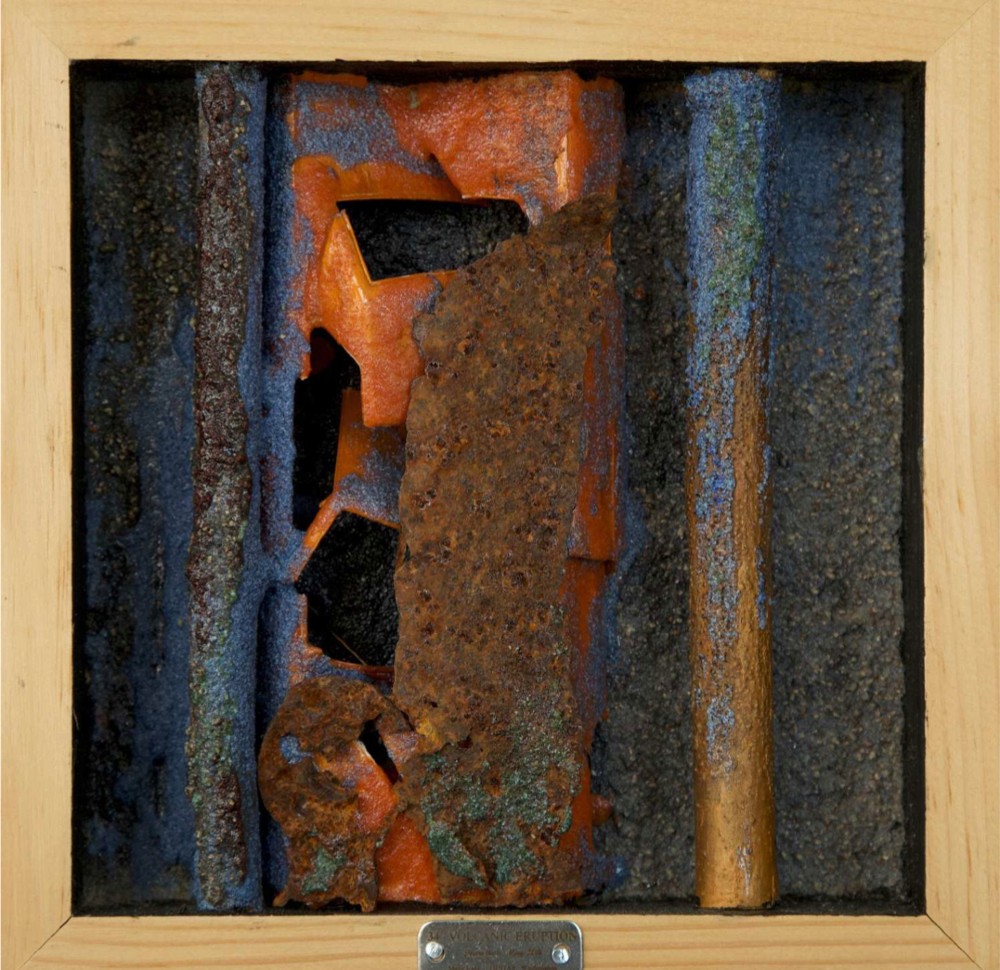

Instead of staying paralyzed, I decided to move. I came up with the absurd idea of going to visit the four disaster sites I talk about in the book: Meta Lake in Washington State, Ben Lomond in California, Seffner in Florida, and Lebanon in Kansas. I wanted my book to have an impact on my life through traveling and meeting people. I then inserted the story of my own experiences on the road into the novel, and it became something entirely different. I also decided to actually create the shadow boxes that Mat makes by using natural materials I found on the sites.

What did you see at each site? Could you tell us about your fieldwork?

There is very little to see at each site, as the disasters happened years, if not decades, ago. In the Florida suburb where a hole opened up under a sleeping man’s bed in 2013, the authorities have demolished the house. No one knows what is going on under the ground, and the land has been sealed off. I wanted to feel the marks, the scars of the earth, whatever the disaster had left behind. In this case, there is a circular patch of lawn that is a different color to the rest of the plot. In researching the volcanic eruption of Mount St. Helens, I found the charred hull of the car on my second visit. That’s when I formed an emotional bond. These places are not spectacular – nothing like Niagara Falls, for example! – but they are emotionally charged.

Have you regained your appetite for fiction?

Partially, at least. I know that my taste for fiction can no longer exist without a connection to reality. The novel I am currently writing, about the Sonoran Desert in California, explores this relationship between fiction and reality. I finished Zones à risques with an encounter with Christian Boltanski, while he was in Chicago, who says: “You’ll never go searching for a completely invented story.”

Zones à risques by Olivier Bodart, Editions Inculte, 2021. 420 pages, 21.90 euros.