Everything could have been perfect between Anna Gould and her husband, Marie Ernest Paul Boniface “Boni” de Castellane. She dreamed of a noble title; he was a count and member of one of the oldest French aristocratic families. She was barely over 18; he was 28 and had already mastered the art of being a gentleman. She was rich and had excellent taste; unfortunately, Boni de Castellane was warts and all – and not much else!

The count enjoyed telling the press that he had visited the United States in 1895 to “discover the country” and, as an experienced sportsman, “to hunt.” He failed to specify exactly what type of game, but his search stopped in Lakewood, New Jersey, where he attended a party at George Gould’s home. This is where he locked eyes with his sister, Anna, whom he had previously met in Paris. The pair met up once, twice, and then traveled to Canada with her family, smiling coyly all the way. Eventually, to everyone’s surprise, Boni de Castellane declared his love. Yet no one had predicted their affair. The young Anna fully exploited the right to ugliness enjoyed by the rich. She was smaller than average, with an asymmetrical face, frizzy hair, a dull, dark stare, a large nose, and even walked with a slight limp. Even in the most elegant finery, she looked like a little monkey dressed as a princess.

When by her side, Boni’s natural distinction was all the more blatant. With a porcelain complexion, lavender-blue eyes, wavy blonde hair, a strong, arched back, a curled moustache, and impeccably manicured fingernails, he was the archetype of the Parisian dandy. It is likely that the young Anna was impressed by this man, who spent more time meticulously tending to his appearance than all the Gould family put together. What’s more, she had desperately wanted to marry at any cost for more than a year. At any cost? The count’s ears pricked up! With the agreement of the two families, the square peg and the round hole were wed on March 4, 1895, in New York City. Two days later, the couple set off for Europe.

Ten Rules to Ruin an Heiress

Boni’s shopaholic side came to light in an exquisite apartment at 9 Avenue Bosquet in Paris, purchased for its weight in gold by the newlyweds. Everything began with two tapestries from the Gobelins Manufactory, inspired by sketches by François Boucher and paid for with 250,000 francs in cash (1,159,000 dollars today). The subsequent purchases were similarly extravagant, including paintings by Rembrandt, Reynolds, Gainsborough, and Van Dyck, furniture from the finest 17th– and 18th-century cabinet-makers, and an array of rare objects. The conjugal apartment was soon too small to contain this collection, which drew jealous glances from the finest museums. Boni’s frenzy reached new heights on April 20, 1896, when the first stone of his future residence was laid on Avenue du Bois-de-Boulogne (now Avenue Foch).

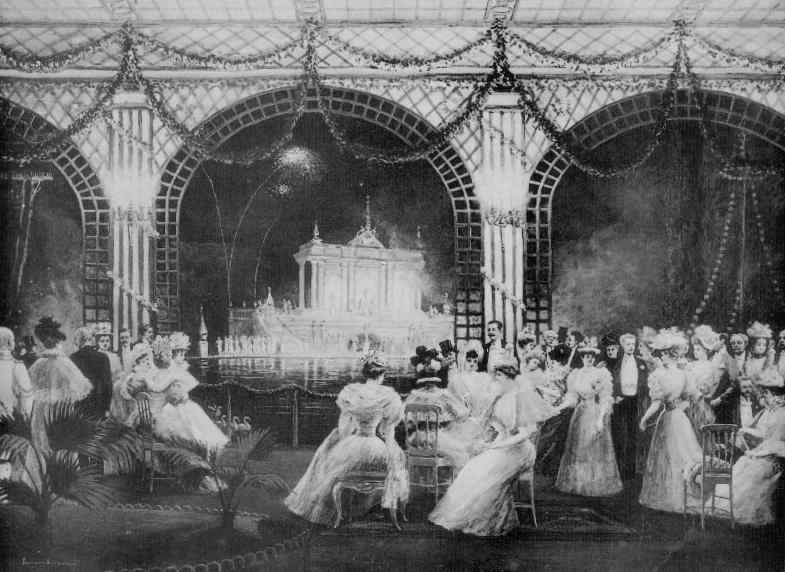

As he found no setting suitable for his own glory, he decided it would be better to build a mansion befitting his taste for grandeur. And who could have been a better model than Louis XIV? Boni commissioned the architect Ernest Sanson to build a 65,000 square-foot residence spread across three floors and inspired by the Grand Trianon at Versailles. The count even traveled to Italy to personally pick the blocks of marble used as a base for the pilasters on the facade of this architectural folly that Parisians later nicknamed “the Pink Palace.” Two-and-a-half years later and three million dollars lighter (almost 100 million today), Boni, Anna, and their first two sons moved into the residence on Avenue du Bois-de-Boulogne. It was in this exceptional setting that the couple hosted the most sumptuous receptions of the Belle Epoque. In celebration of his wife’s 21st birthday, Boni, who boasted that he was Talleyrand’s great-grandson, set the tone on July 2, 1896, by recreating the fifth day of festivities held in honor of Louis XIV’s wedding with Maria Theresa of Spain.

In 1897, the couple acquired the Walhalla, a 230-foot, three-masted steam yacht, for the trifling sum of 200,000 dollars (6,6 million today): a “superb opportunity,” according to Boni. The ship had a crew of some 100 men under the orders of a captain and four officers. The same year, Anna Gould fell in love with the Château du Marais, in the Essonne département, built in 1770. The count saw potential in the estate, especially as it was only 30 miles from Paris. Hang the expense! And as it had belonged to his distant ancestors, Boni also bought the Château de Grignan in Southern France in 1902, hoping to restore it.

As a royalist and fervent opponent of Alfred Dreyfus, Boni launched his political career in 1898. This saw him spend an additional 300,000 dollars (almost 10 million today) to lead his campaign and become the representative of the Basses-Alpes département. His voters often enjoyed a little too much of his generosity, and the count de Castellane’s electoral victory was twice rejected on the pretext that he had bought the votes of the inhabitants in his ward.

From Fairy Tale to Nightmare

Worthy of the grandest monarchs of the Ancien Régime, the count and countess de Castallane’s lifestyle was so lavish that they burned through 7.7 million dollars (251 million today) in the first five years of their marriage. The international press went wild and American psychiatrists began studying Boni’s personality. They even came up with a name for his behavior: coenaesthesis. The Goulds tried to regulate the couple’s spending, although without attempting to understand it. In 1900, Anna was placed under the guardianship of her brother, George, and her debts (she had dipped extensively into her capital, despite the fact that she was supposed to live on the interest alone) were spread out over several years of repayments.

Boni was outraged at being reduced to live on an annual allowance of 300,000 dollars (less than 10 million today). Meanwhile, Anna had grown tired of her spendthrift, quarrelsome, vain husband. Above all, she hated his numerous affairs and the rumors he spread about her. When leading a visit around their first apartment, Boni found it amusing to describe their bedroom as the “expiatory chapel,” and the “other side of the coin.” Encouraged by her family, she finally divorced in 1906 and took her revenge in 1908 by marrying Boni’s cousin, Duke Hélie de Talleyrand-Périgord, with whom she had two children. Boni, ever the comedian, became an antiques expert and wrote his memoirs under the title The Art of Being Poor!

Pour le plaisir et pour le pire : La vie tumultueuse d’Anna Gould et Boni de Castellane by Laure Hillerin, Flammarion, 2019.

Article published in the December 2021 issue of France-Amérique. Subscribe to the magazine.