The 19th-century artist James Tissot’s name is emblematic of his English Channel-spanning life and career. With a foot in two cultures, a style that refuses categorization, and a dramatic late-career shift in subject matter, he is hard to pin down. That may explain why Tissot, who was famous in his lifetime, is not more familiar to modern-day audiences. James Tissot: Fashion & Faith, which opens this month at San Francisco’s Legion of Honor, posits that his oeuvre is ripe for reassessment. The first major international exhibition of his work in two decades, it brings together some 60 paintings, as well as prints, drawings, photographs, and cloisonné enamels.

The show draws on new research findings gleaned both from high-tech analyses of individual paintings and from a trove of documents, photographs, and personal effects preserved at the privately owned château where Tissot spent his final years. “I think for people that are kind of specialists in the 19th century, there’s that new scholarly depth, and for a lot of people Tissot will just be a revelation,” says Melissa Buron, co-curator of the exhibition and Director of the Art Division at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

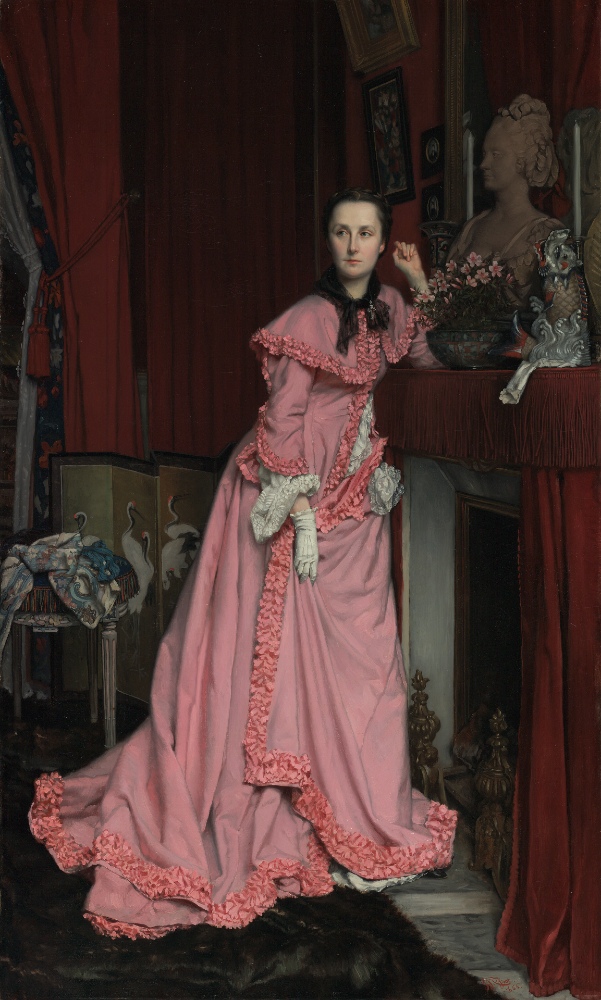

Jacques Joseph Tissot was born in Nantes in 1836 to parents whose involvement in the textile and millinery businesses likely planted the seeds for what would become one of the hallmarks of his work: a keen interest in fashion and a virtuosic ability to render its textures, patterns, and frills. His father disapproved of his creative inclinations, but with his mother’s help he moved to Paris in 1855 and was trained in the Academic tradition by disciples of Ingres.

Tissot debuted at the Paris Salon in 1859; that same year, he would demonstrate his Anglophilia by adopting the name James. In the 1860s, he shifted his focus from historicizing scenes to the depictions of modern life in fashionable society for which he is now best known. Thanks to regular Salon exhibitions and a fruitful relationship with a major Paris art dealer, he was soon ensconced in posh quarters.

Everything changed with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Tissot remained in Paris and took part in the conflict as a member of the National Guard, all the while sketching the horrors to which he bore witness. After the war, he relocated to London, perhaps fleeing suspicions of involvement with the short-lived left-wing Commune. There, after being introduced into society by the editor of Vanity Fair, to which he contributed political caricatures, he proceeded to enjoy even greater commercial success than he had in Paris.

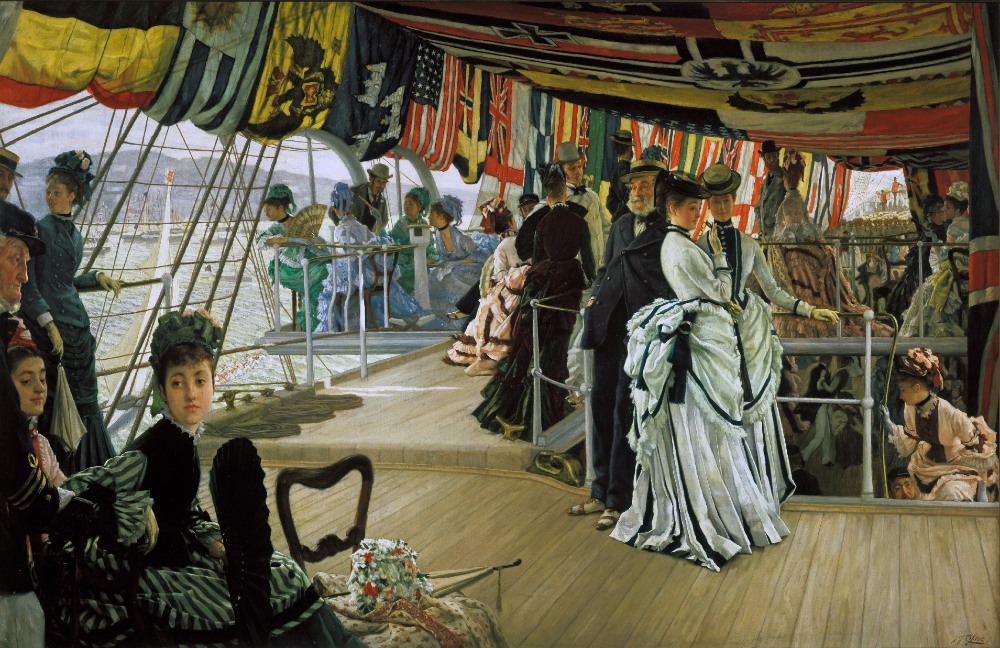

Tissot’s meticulous renderings of shipboard balls and elegant picnics have a superficial air of frivolity yet convey enduring human truths to the astute viewer. One reviewer observed that he was “looked upon over here as a kind of artistic Zola.” While in London, Tissot declined an invitation from Degas to participate in the first exhibition of the group now known as the Impressionists. The most defining aspect of this period was his long relationship with a young Irish divorcée named Kathleen Newton, model and muse for many of his paintings.

When Newton succumbed to tuberculosis at age 28, a grief-stricken Tissot decamped almost immediately back to Paris and would later, as was common practice at the time, seek to commune with her through a medium. One of the highlights of the exhibition is the pairing of a mezzotint titled The Apparition with the recently rediscovered painting on which it was based; they depict Newton’s ghost and a spirit guide as Tissot professed to have seen them during a seance.

To re-establish his foothold in the local art market, he began a series of 15 large-scale paintings titled La Femme à Paris, representing the various pursuits of society women. But while researching The Choir Singer in the Church of Saint-Sulpice, he had a religious vision that inspired him to dedicate the final two decades of his life to Bible illustration. He made three trips to the Holy Land and eventually produced 350 water-colors depicting the life of Christ but died before completing his Old Testament series.

Religious art may have fallen out of fashion, further accounting for Tissot’s lack of name recognition nowadays, but The Life of Christ was a blockbuster in its day, earning the artist as much as his previous 30 years of work. “[The watercolors] went on a tour of the United States, and they were so spectacularly fascinating to people that there are newspaper reports about visitors weeping as they went through the rooms,” relates Melissa Buron. “There was a revival of interest in religion, and cinema was something that wasn’t so widely available yet… It was almost like going to see Avatar [James Cameron’s sci-fi movie in 3D format] at the end of the 19th century.” In fact, these sequential images have influenced biblical films from D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance to William Wyler’s Ben-Hur and at least one hit movie outside of that genre: Tissot’s Ark of the Covenant is the model for Indiana Jones’s.

James Tissot: Fashion and Faith

From October 12, 2019, through February 9, 2020

Legion of Honor

San Francisco

From March 23 through July 19, 2020

Musée d’Orsay

Paris

Article published in the October 2019 issue of France-Amérique. Subscribe to the magazine.