“I experienced the excitement of the Harlem Renaissance,” recalled Ada “Bricktop” Smith, an African American singer who moved to France in 1924. “But in Paris, it was even more amazing. The entire city was celebrating. The war had been terrible for the French, and now that it was over, they wanted to forget the whole thing – just party and dance.” After performing at several cabarets in the French capital, Smith opened her own club, Chez Bricktop, at 66 Rue Pigalle (its entrance was set off by a graceful wrought-iron awning, while a portrait of the proprietor reigned over the vestibule). For 15 years, this elegant establishment featured the world’s top jazz musicians. Smith became the go-to person for many American Blacks who sought refuge in the capital between the two World Wars, and helped make jazz a success in Paris.

Harlem on the Butte

It was in fact the military that brought jazz to France. In 1917, the U.S. Army began drafting Black soldiers. The 369th Infantry Regiment – the African American unit known as the Harlem Hellfighters – remains a symbol of Paris’s first liberation. Along with its formidable combat skills, the regiment was renowned for its jazz band, led by James Reese Europe. At his first concert in Paris, Europe recalled, “the audience went crazy even before the second piece!” The band was hugely successful. An album recorded by Pathé Studios was the first jazz record to be released in France. Europe, who became a major figure on the New York music scene after the war, was stabbed to death in 1919 following an argument with one of his band members. But ragtime had reached the Old World.

While the Harlem Hellfighters returned home after the war, some African American musicians decided to stay in France. Their wartime experiences had been a wake-up call. Discovering a continent without racial segregation had intensified their desire to fight inequality. For those who stayed, Paris was a place of freedom.

Several of these Black artists – Louis Mitchell, Arthur Briggs – settled in the French capital, but one of the most important was Sidney Bechet, who arrived in France in 1925 to play with the Revue nègre. Bechet adored Paris, and he soon became the toast of the town. “Whenever I walked down the street,” he said, “I would meet four or five people I knew – incredible talents. At night, there was always a singer or a musician to go see. I never went to bed before 10 a.m.” Known for his feisty temperament, Bechet wandered the streets of Montmartre and frequently got into trouble. One night, after playing at Bricktop’s, an argument broke out with pianist “Little Mike” McKendrick. Tensions rose, and the two men faced off. Bechet was armed. The clarinetist was sentenced to 11 months in jail.

The best-known American artist of that era was without question dancer Josephine Baker. A performer at the Revue nègre, where she worked with Bechet, Baker appeared virtually nude, clad only in her famous banana skirt. Both humorous and sexually provocative, she shocked and amused her audience. A complex personality, the “Black Pearl” single-handedly embodied the ambiguous situation of Black artists in Roaring Twenties Paris. While the French – who were discovering new sounds – considered her a symbol of open-mindedness, she also reflected a taste for exoticism often tainted by racism and colonialism. At the height of her fame, Baker was criticized by a number of Caribbean activists including Jane Nardal, who saw the dancer’s popularity as rooted in racism. Flattering French ethnocentricity while conveying a subversive message, Baker became a case study for historians on both sides of the Atlantic.

Bebop in Saint-Germain

In the shadow of the American artists, a French jazz scene emerged. The Hot Club of France, an association of jazz lovers, was established in 1932, and would organize the Paris tours of such American musicians as Coleman Hawkins and Duke Ellington. In 1934 it formed its own quintet featuring violinist Stéphane Grappelli and guitarist Django Reinhardt; it subsequently launched a competition for France’s best musician. During World War II, French jazz continued to develop, albeit clandestinely. The leaders of the Hot Club mounted a smuggling operation to ensure the circulation of records between Free and Occupied France. Meanwhile, musicians played in secret dives.

“In 1945,” composer Michel Legrand recalled, “I went to a Dizzy Gillespie concert. It was a bolt from the blue. Jazz had been banned during the Occupation, and suddenly, in a single evening, this extraordinary bebop band revolutionized my way of understanding music. At night, I began hanging out in the clubs of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.” Michel Legrand had a point: American jazz had evolved since it was first heard in France. These were the days of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. Prewar swing sounds were eclipsed by the complex beats of bebop. Improvisations went on longer. Tempos were fast, sometimes dizzyingly so, and the musicians were virtuosos.

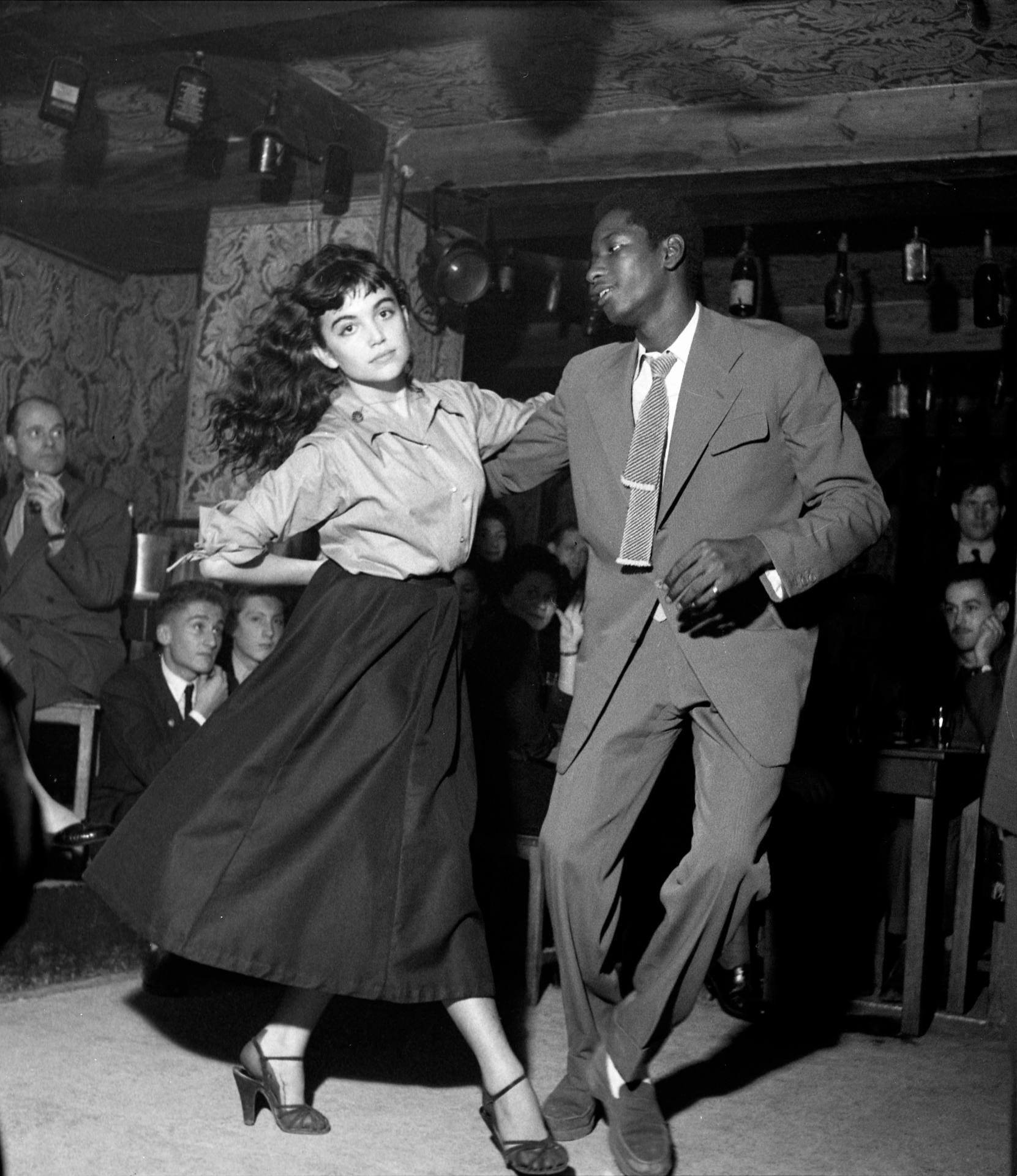

The liberation of Paris brought Americans back to the French capital. Saint-Germain-des-Prés became the new epicenter of Parisian nightlife, the charleston gave way to bebop, and jazz aficionados rubbed shoulders with Existentialists. Several clubs – Le Vieux Colombier, Le Club Saint-Germain – opened on the Left Bank, frequented by intellectuals who saw the African American community and jazz as possible modes of resistance to American imperialism. One winter evening, the singer Juliette Gréco was in a café on Rue Dauphine. She took off her coat and laid it on a staircase bannister. When it fell to the ground, she bent to pick it up – and caught a glimpse of a fantastic vaulted cellar. She liked the place, and it soon became Le Tabou, another legendary club frequented by Saint-Germain-des-Prés’s jazz fanatics. Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre became regulars. Boris Vian and his trumpet were stars. Nocturnal jam sessions attracted an underworld crowd.

This was the atmosphere that drew some 500 Black artists to Paris. Like those who had led the way in the 1920s, they left the U.S. to show their opposition to segregation, but also to get away from “the show business vultures,” as saxophonist Lucky Thomson put it. Among them were such major bebop stars as Don Byas, Bud Powell, and Dexter Gordon. Drummer Kenny Clarke was instrumental in introducing bebop to French musicians. In 1956, he settled permanently in Paris, giving drumming lessons and playing with his compatriots when they came to France. It was partly thanks to Clarke that in 1957, bass player Pierre Michelot and pianist René Urtréger toured with Miles Davis and joined him on his recording of the original soundtrack of Elevator to the Gallows.

For post-bop jazz artists, Paris remained a special destination. Many composed avant-garde music, and they found French audiences to be particularly receptive to their experiments. In 1969, the principal members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), Lester Bowie, Roscoe Mitchell and Anthony Braxton, came to the French capital from Chicago. Bowie had been performing with a painted face and wearing African clothing for years, and the presence of so many African musicians in Paris was deeply inspiring to him. After spending time in the city and playing at the Lucernaire, in Montparnasse, these free jazz masters decided to move to a farm in nearby Saint-Leu-La-Forêt.

The members of the AACM left France in 1971. With a few exceptions, their departure marked the end of the American presence in Paris. Saxophonists Archie Shepp and David Murray still live there, but most American musicians only come on tour.

French Jazz Musicians in America

For their part, French jazz musicians dreamed of America. In 1946, Duke Ellington invited Django Reinhardt to tour with him. They started off in New York. The second evening, the guitarist ran into boxer Marcel Cerdan, the two friends went out for drinks, and Django arrived at the end of the concert without his guitar. Things improved after that, but the guitarist often spoke bitterly about his American experience.

After Reinhardt, other French musicians performed in the U.S. Pianist Martial Solal gave a historic concert at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1963. But complicated regulations made touring difficult. Bassist Jean-François Jenny-Clark reportedly had to interrupt a concert at New York’s Village Vanguard in the 1980s because union quotas hadn’t been respected and there weren’t enough American musicians on stage. He ended up having to go back to Paris.

Nowadays, the French musicians performing in the United States are mostly in their twenties, thirties and forties. Since the 1990s, a number of them have chosen to spend time in the U.S. to gain jazz experience. “Here,” explains Guilhem Flouzat, “you learn by watching, by playing with exceptional musicians.” This young drummer arrived in New York six years ago with a scholarship from the Manhattan School of Music. He hopes to stay longer, “to get the most out of meeting people.”

Some older musicians have moved to the U.S. for good. Pianist Jean-Michel Pilc, who has played with the greats – Roy Haynes, Michael Brecker, Marcus Miller – has made America his home for the past 25 years. His style, his reworking of jazz classics, make him a major pianist on the contemporary scene. Another key figure is saxophonist Jérôme Sabbagh. Born in Paris, he lived in Boston before moving to New York. His latest album, The Turn, recently came out on Sunnyside, an American label run by a Frenchman.

Organized by various Paris-based partners, the French Quarter Festival this in January 2015 offered a moving epilogue to this transatlantic history. The top names in French jazz – Airelle Besson, Cédric Hanriot, Olivier Bogé – all performed at New York clubs. On the third evening, the show at Dizzy’s Club wrapped up with René Urtréger’s trio. That evening was particularly emotional for Urtréger. A bop pianist who had appeared with Kenny Clarke and Miles Davis, “le Roi René” had never played in New York. At age 80, he finally made his debut in the Big Apple.

Article published in the May 2015 issue of France-Amérique. Subscribe to the magazine.