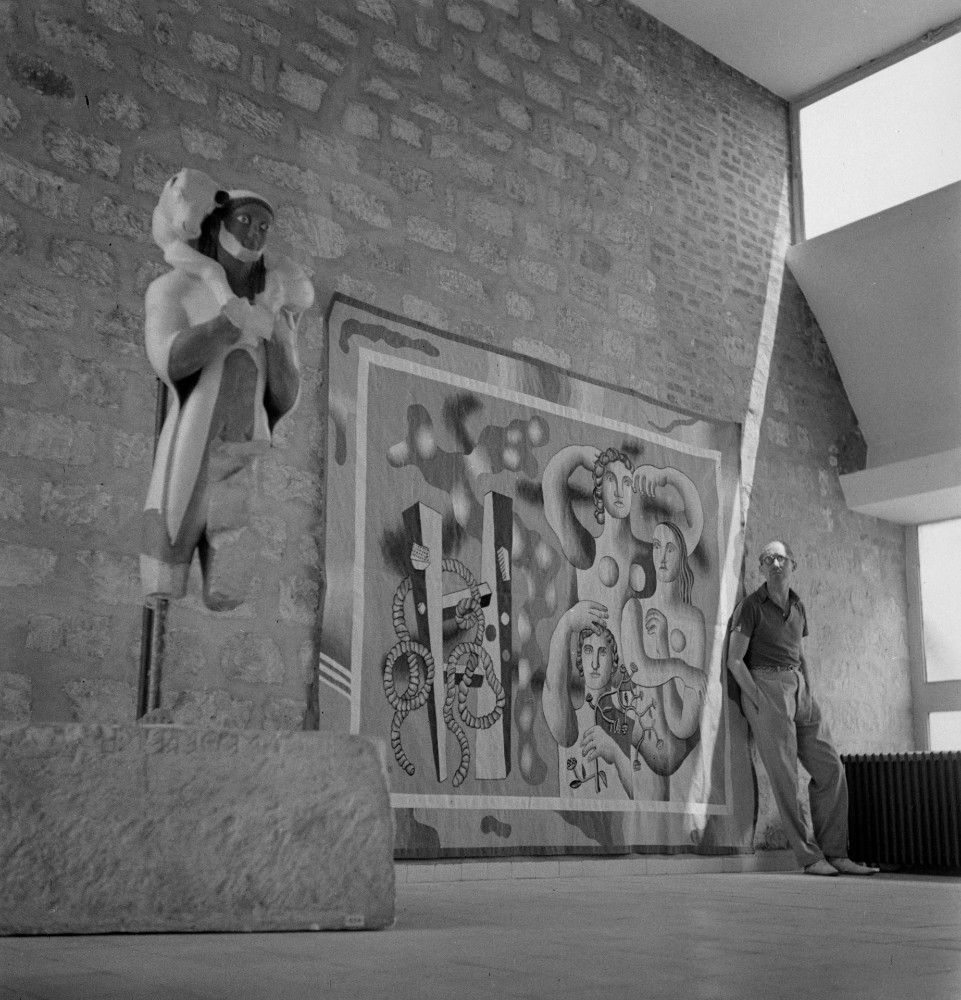

It is easy to imagine Marie Cuttoli standing proudly in a fashionable Manhattan gallery, watching the New York elite as they swoon over her latest achievement – revisiting modern art through tapestry. The petite, elegant brunette in her fifties, sporting a short bob and a lock of white hair, was a discreet pioneer. Encouraging a dialogue between pictorial and applied arts, the French businesswoman presented a series of 17 striking works in Manhattan in 1936. The panels of wool and silk woven by the ancestral workshops of Beauvais and Aubusson broke from the motifs and colors of Renaissance and Baroque artists, instead welcoming the likes of Picasso, Georges Braque, Raoul Dufy, and Matisse. And they were all created specially for the collector herself! The revolutionary art of these modernist masters had been transformed. Mellowed by the more flexible medium, the lines of cubism and the bright, post-Fauvist colors took on a gentler aesthetic, while the surrealist flourishes became more tangible. The daring gallerist’s gamble had paid off: She won over the American public. After being relegated to an illustrious but old-fashioned golden age, the artistic tapestries inherited from royal workshops made a remarkable comeback in the 20th century.

Cuttoli played a vital role in opening modern art to new forms of expression, as shown at the major exhibition currently hosted by the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, Marie Cuttoli: The Modern Thread from Miró to Man Ray, which will run through August 23. “She was an entrepreneur who […] had this vision for how she was going to affect the discourse on modern art,” says Cindy Kang, assistant curator at the Barnes. But because her work was “crossing categories,” it “falls through the cracks easily because of the way we study art history and the way we train to be curators.” With the current renewed awareness of the roles of women throughout history, particularly in the arts, “this is the kind of story that we are more ready to appreciate.”

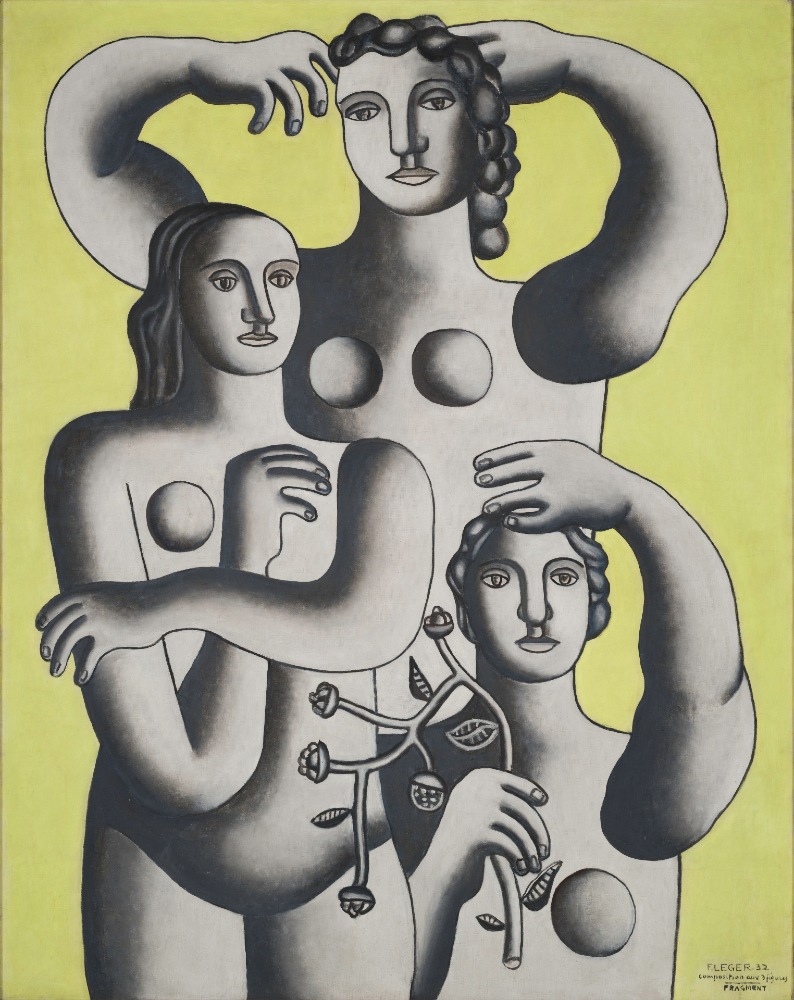

Cutolli, the daughter of a soda salesman from Tulle, moved to the avant-garde Paris of the inter-war period with her family when she was a teenager. After meeting a lawyer and politician from Constantine, whom she married in 1920, the young woman split her time between Paris and Algeria, where she launched her first business making woven carpets in the medina, inspired by the works of modern artists. In 1922, she founded her brand Myrbor, a forerunner of today’s concept stores, which sold carpets and other decorative objects, as well as works by the masters and couture clothing made in collaboration with artists such as Russian painter Natalia Goncharova. Whether featured on floors, walls, or in clothing, the idea behind her creations was the same: using textiles as an alternative, changing form of expression for modern art. “If you like to see a Léger or a Lurçat or a Picasso on your walls, you will like to wear Myrbor clothes,” wrote sisters Thérèse and Louise Bonney in a 1929 shopping guide for Americans in Paris.

Cuttoli made a name for herself on the cultural scene during the 1930s. She was a “great friend” of Picasso, in the words of the painter’s muse, Françoise Gilot, and featured in Man Ray’s photographs in Shady Rock, her villa near Antibes, alongside Dora Maar and her husband Paul. Other images show her with poet Paul Eluard, socialist leader Léon Blum, and American businesswoman Helena Rubinstein. Inspired by the needs of the struggling weaving industry, she used her business sense and network to develop her modernist art project. Picasso was one of the first figures she convinced, and others soon followed. A 1939 exhibition of tapestries and modernist objects loaned by Cuttoli to the San Francisco Museum of Art attracted more than 10 million visitors.

Originally set to run for several months, the start of World War II and the closure of national borders saw the show transform into a touring exhibit, traveling to Honolulu, Detroit, Cleveland, and Massachusetts. Cuttoli had “quite a considerable” impact, says Jean-Louis Andral, director of the Musée Picasso in Antibes. In his eyes, she became an “ambassador of French and European culture in the United States,” who enabled artists to find news ways to “access an audience that would never have known about them” without her. During the war, the businesswoman found refuge in America with the help of Dr. Barnes, a renowned art collector and philanthropist in Philadelphia.

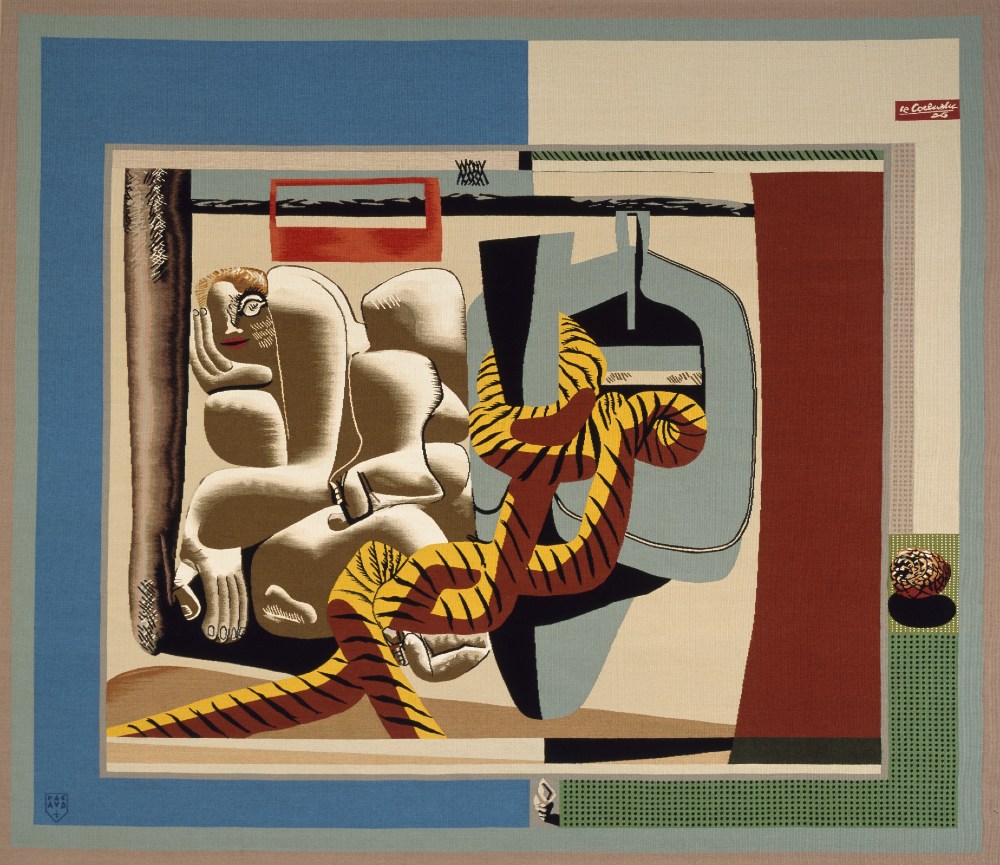

But after 1945, Cuttoli was slowly forgotten. In the United States, “there was this heroic narrative of American abstract expressionism that very much dismissed the French tapestry tradition because they thought it was feminine, they thought it was decorative,” says Kang. Meanwhile, in Europe, artist Jean Lurçat and architect Le Corbusier, with his muralnomad concept (a movable mural décor made with acoustic and thermal insulation), were pushed into the spotlight. Cuttoli’s contribution was significantly played down and even criticized, seen as overly timid in her reinvention of a medium seeking to be independent from painting or any other genre imitation. In 2020, along with Kang, a new generation of American exhibition curators and art historians have however advocated for a reassessment of Cuttoli’s influence. After all, the United States is where her work enjoyed its greatest success.

Marie Cuttoli: The Modern Thread from Miró to Man Ray

From July 25 through August 23, 2020

The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

Article published in the June 2020 issue of France-Amérique. Subscribe to the magazine.