France-Amérique: Is the fall of Kabul the sign of America’s decline? And can we compare this situation with the United States’ disastrous campaign in Vietnam?

Gérard Araud: The fall of Kabul would represent the decline of the U.S. empire if Afghanistan was of strategic interest to America. However, it is not. The current world order has not been affected by recent events and the factors governing America’s power have not shifted in the slightest. Just like in Vietnam, the U.S. gradually found itself trapped in an ultimately peripheral conflict. Fighting Al-Qaeda – the original objective – did not require spending almost two trillion dollars.

Should we expect increased American isolationism, most likely supported by the U.S. public?

American isolationism began under Obama, accelerated under Trump, and is continuing under Biden. The three presidents understood their citizens’ diminishing patience for interminable, costly, and ineffective foreign interventions. Of course, true isolationism is impossible in a world made so small by technology, but the time of America as the world’s police is coming to an end. The United States will now only intervene to defend their essential interests, and will have a very restrictive vision of what these are.

The Islamists must be celebrating. Should we fear a return of terrorism to both Muslim countries and the West?

It would be a mistake to consider what has just happened in Afghanistan as an Islamist issue, in the same way the Vietnam War should not have been viewed as a fight against communism. These broad brushstroke interpretations lead to failure because they ignore local factors and the influence of regional players. Three years after the fall of Saigon, the Vietnamese, the Cambodians, and the Chinese – all communist countries – were fighting each other. We should analyze each conflict in light of its specific characteristics instead of reducing it to an overly simplistic equation.

Is America’s failure one of neoconservatives who wanted to export democracy? Or is it down to local factors specific to Afghanistan, a country that historians have nicknamed “the graveyard of empires”?

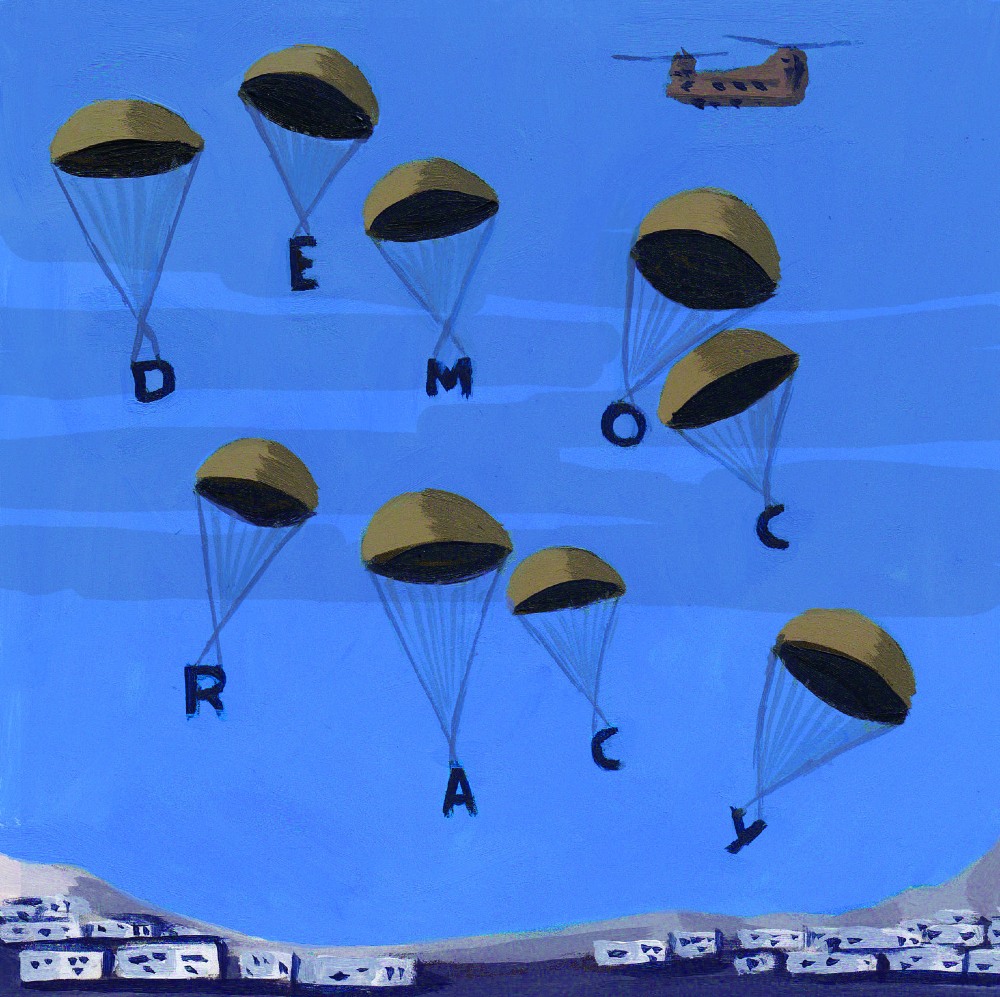

America’s failure – trying to artificially construct a nation without taking into account local traditions – is one of promethean proportions. The neoconservatives, led by George W. Bush and Dick Cheney, thought that every country aspired to become a liberal democracy, and that organizing elections would make everything better. They forgot that it took more than two centuries for democracy to become the norm in Europe. They didn’t want to admit that it takes more than elections, but rather requires an active civil society, a high-quality press, and the acceptance of differences. We can observe a similar failure in Iraq, despite the country’s established, urban middle class. You cannot simply air-drop democracy – especially into a country as archaic and religiously and ethnically fragmented as Afghanistan.

Are the French forces in the Sahel region more skilled than the Americans in the Middle East, given that they have a better understanding of local cultures?

I fear that, sooner or later, the French will meet the same fate in the Sahel as the Americans in Afghanistan: a theater of operations that is just as geographically challenging, societies that are unwilling to embrace modernity and democracy, extreme poverty, and no perspective of victory. Let’s not forget that every foreign army of liberation becomes one of occupation in time.

What does this mean for the world order?

The world has always been in disorder. After the American-Soviet duopoly that held sway until 1990, and after the subsequent American monopoly, the world is once again founded on traditional rivalries between major and medium-sized powers. It is pre-1914 Europe on a planetary scale. The difference is that the Europeans had shared concepts and languages to manage their rivalries – although this did not stop World War I. Today, rival powers have no common tradition that might prevent misunderstandings and incidents. We therefore need old-school diplomats such as Talleyrand, Metternich, and Kissinger to try to create a dialogue between rivals and achieve a modus vivendi which, while recognizing the reality of confrontations between world powers, would also instate mechanisms to avoid the worst from happening. All parties must be aware of each other’s limits.

Should Taiwan, South Korea, and Israel worry about America abandoning Afghanistan? And should China, Iran, and Russia be pleased?

Afghanistan will above all be an example of a useless operation, pointlessly prolonged and catastrophically concluded. No one can view America’s withdrawal from this secondary country as a lesson for the United States’ rivals or allies.

Has the time come, once again, for Europe to build a military intervention force independent from NATO?

Aside from a potential migratory crisis at a particularly inconvenient time in the context of upcoming elections in Germany and France, the fall of Kabul should not have any immediate consequences in Europe. Many are grumbling that the United States did not first consult with its allies, but it has never sought advice before making major decisions. What’s more, the Europeans have always made their peace with this modus operandi, and will do so again because they are deeply attached to America’s protection. Washington’s off-handed approach to Europe is the premium on an insurance policy that they want to preserve at any cost. However, in the wake of Obama and Trump, the Europeans should understand that they can no longer rely on America for anything beyond the guarantees afforded by NATO. In other words, the world’s police are going home, and it is now Europe’s job to manage Ukraine, Syria, Libya, and the Sahel, the regions burning on the doorstep of their continent. Europe can also no longer expect the arrival of G.I. forces or Tomahawk missiles. Are they ready? Regardless of Emmanuel Macron’s warnings, I fear not. Western Europe has spent too long sheltering under the Stars and Stripes to want to leave; it would be too costly and too risky. This will only happen if Europe is forced, and this is not yet the case. It will therefore cling to NATO more than ever and adopt an increasingly hostile view of a European intervention force – especially as the United Kingdom will do everything in its power to sabotage this effort from the outside. If the fall of Kabul is a warning, it is paradoxically more for Europe than for the United States.

Henry Kissinger : Le diplomate du siècle by Gérard Araud, Tallandier, October 7, 2021.

Interview published in the October 2021 issue of France-Amérique. Subscribe to the magazine.