It’s rare for a translation issue to become a news item, still less an international headline-grabber. But of course, everything depends on the choice of words, and – more important – the person using them. When the president of France said in a recent interview that he wanted to emmerder the country’s vaccine refuseniks, he unleashed what could be politely called a fecal tempest at home and sent foreign journalists scurrying to their dictionaries or databases to decipher exactly what the expression meant.

Let’s take a moment to consider the problem. Whatever the source language, one of the hardest things to translate is informal speech, especially slang, which lurks in the undergrowth of the official lingua franca. Many vernacular expressions are coined by specific communities or professions with a shared interest, be they butchers or burglars, who want to exclude outsiders. Above all, slang evolves naturally: As any parent knows, repeating a slangism used by your kids will lead to eye-rolling, “uncool dad/mom” complaints, and immediate replacement of the outed expression. Likewise, many slang words belong to a specific era or milieu, making it hard to translate authors like, say, Louis-Ferdinand Céline or Damon Runyan, who were of their time. Possibly the hardest job is to find exactly the same register: When asked to translate something as seemingly simple as “How’s it hanging?”, should you go for Ça va ?, Ça boume ? – or something close to the literal American meaning? (Good luck with that.)

Getting back to President Macron, his actual words on unvaccinated people were J’ai très envie de les emmerder. The problem here is that emmerder comes from the noun la merde, which bilingual glossaries render as “shit.” Now, even someone unfamiliar with French would doubt that Mr. Macron wanted to daub delinquents with excrement. In fact, the verb for the act of defecation is chier (which, despite, the resemblance with “shit,” comes from Latin, not Old English). And it is seen as more vulgar than emmerder, which has become distanced from its literal sense.

So what exactly does the word mean, and why is it difficult – and often perilous – to translate? While French dictionaries offer definitions using verbs like importuner fortement (seriously harass) and agacer (irritate), the source word nevertheless contains that scatological element which resonates to a French ear. Some American news anchors and journalists, possibly concerned with their audiences’ sensibilities, opted for the verb “to annoy,” which echoes the French verb ennuyer. The Associated Press agency went for a timid “to bug,” while CNN decided on “to really piss off,” which is closer to the original sentiment (we’ll pardon the split infinitive). Maybe because of CNN’s standing, or for want of a better alternative, a large section of the English-language media adopted the term, though The New York Times did specify that the original French word was more vulgar. (An exemplary demonstration of why translators should always work into their native language was given by a French journalist, who ran the phrase through an online translation tool and found that Mr. Macron wanted to f*** the unvaccinated.)

Translation aside, why did the normally smooth-tongued Mr. Macron deliberately use a word that he knew was bound to shock? After all, this is the man who cast himself as a “Jupiterian” president, standing loftily above the grubby grind of ordinary politics. Yet since the start of his term, Macron’s habit of using salty language and seemingly throwaway remarks has become something of an unfortunate trademark, earning him the ire of his opponents and the embarrassment of supporters. Slang phrases like un pognon de dingue (roughly “a crazy amount of cash”) or off-the-cuff comments calling the French Gaulois réfractaires (rebellious Gauls) or fainéants (idlers) have marked his five-year presidency. These and other infelicities were gleefully recalled by media outlets reporting the emmerder outburst. In parallel, Mr. Macron’s political enemies and adversaries decried his “vulgarity” and called his choice of words an “unpardonable error.”

It is undeniable that political rhetoric in France has coarsened over the past two decades, a trend that one parliamentary veteran describes as the descent from verbiage to vulgarity. Ignoring Mark Twain’s adage that profanity should be left to skilled and well-trained professionals, many elected representatives use merde and its cohorts as if they were commas or periods. Of course, it is not just French politicians who are resorting more frequently to profanity. In the U.S., data analysis shows that the use of expletives by members of Congress rose steadily during the 2010s. And presidential profanity is a long-standing tradition, from Richard Nixon’s “expletives deleted” to Joe Biden’s recent – and very public – “SOB.” Of course, all records were broken when Donald Trump took office: Instances of the S-word in particular soared after the president used it to describe Haiti, El Salvador, and various African countries.

However tempting it may be to conclude that Macron was consciously or unconsciously channelling his inner Trump, there are a couple of more likely explanations for his choice of language. The first relates directly to the Covid pandemic and the growing resentment expressed by the vaccinated against the “tiny minority” of French people who refuse to be inoculated. By employing a turn of phrase often used insolently or angrily – Je t’emmerde (Screw you!) is a common rejoinder – President Macron is tapping into that popular sentiment and throwing down the gauntlet. According to one academic linguist, the choice of a deliberately transgressive word by a very powerful person – specifically, when a head of state breaks ordinary language rules – is a signal that a demonstration of strength is underway. In other words, vaccine holdouts will get either a shot or a boot in the backside.

The second explanation for the word choice is the president’s desire to be relatable to voters. He has long been seen as an urban elitist who is out of touch with the ordinary people whom he is supposed to serve, someone who uses phrases like les gens qui ne sont rien (worthless people) to describe the unsuccessful, and who has publicly described his country as unreformable. Now, with a presidential election due in April, Mr. Macron may be trying to talk folksy in order to seem accessible. (Later on in that infamous emmerder interview, he used down-home phrases like aller au ciné, “go see a movie,” and prendre un canon au bar, “grab a drink at the bar.”) A president shouldn’t talk like that. But a candidate most certainly should.

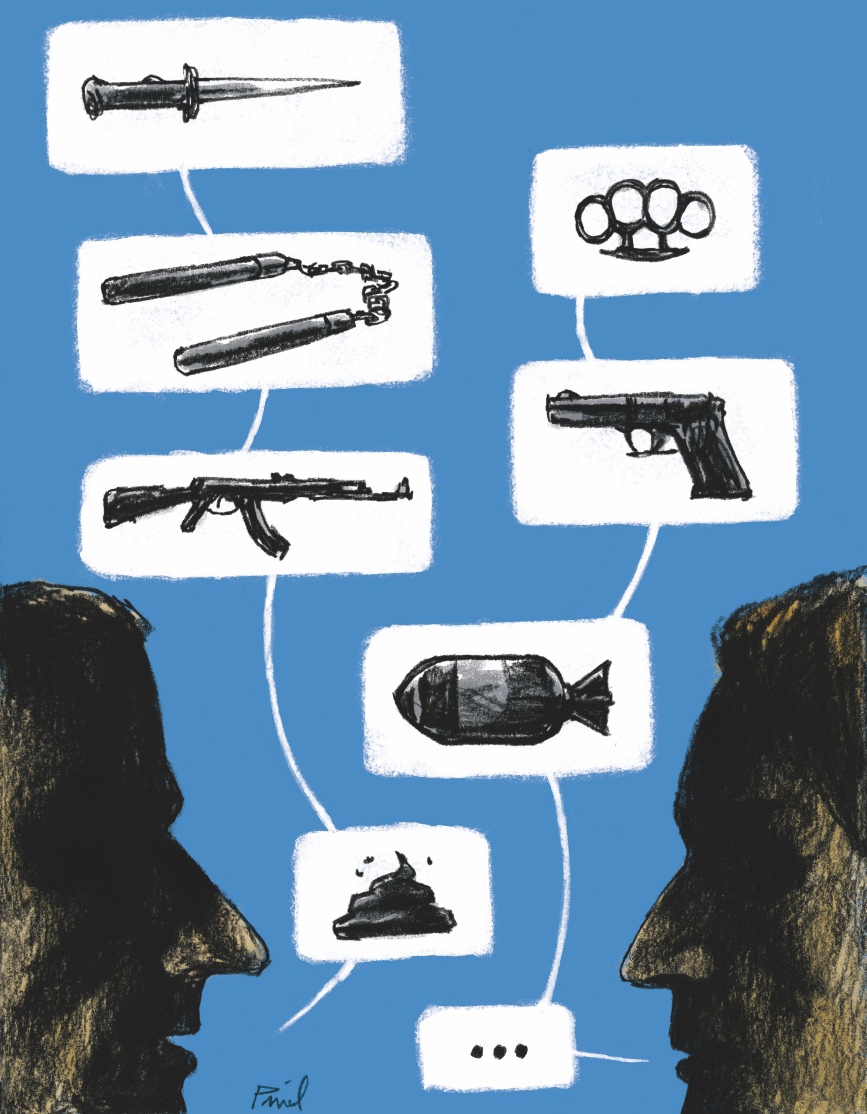

Be that as it may, the ruckus over Macron’s choice of words underlines what is happening to our political language. In the words of a French editorialist, “to offset the powerlessness of their actions, politicians tend to inflate the power of their words. The problem is that they keep adding more chili to an already spicy stew.” And we all know what that can cause, don’t we?

Article published in the March 2022 issue of France-Amérique. Subscribe to the magazine.