Back in 1970, the United States was governed by a two-speed food system. Supermarkets were gradually crowding out local grocers, and homemakers’ shopping carts were overflowing with standardized, industrial products such as cans of Campbell’s soup, Kraft macaroni and cheese, and loaves of sliced Wonder Bread. On the other end of the spectrum, an obsequious, well-heeled clientele continued to champion the only cuisine they thought was worth eating, French haute cuisine, which had remained practically unchanged since Escoffier.

It was during this time that Julia Child – who had just published the second volume of her best-seller Mastering the Art of French Cooking – and her husband Paul set off for Provence. They had arranged to meet their friends in their vacation home a few miles from Grasse for the holidays. Guests included the cheery and chubby-cheeked James Beard, who was delighted to leave the clinic where he was undergoing weight-loss treatment, self-taught chef Richard Olney, who lived in a village northeast of Toulon, and New Yorker journalist M.F.K. Fisher, the author of The Art of Eating, who had spent several years in Dijon and Aix-en-Provence.

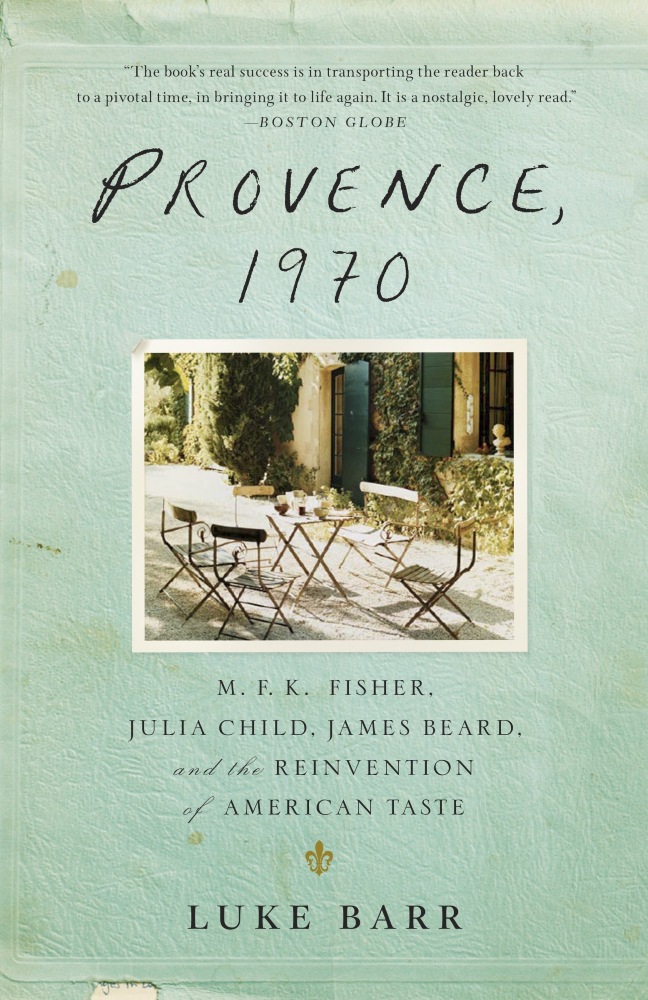

“Provence is where it had all started,” writes author Luke Barr, M.F.K. Fisher’s grandnephew, in Provence, 1970, the book he devoted to this elite encounter between the leading gourmet group of Francophile American food writers. “It was a place that epitomized the food-centered culture and philosophy the group stood for, a place where life and cooking and style all intertwined so easily.”

The life of the household was punctuated with lunches, trips to local greengrocers and cheese shops, and visits to Cannes, the Maeght Foundation in Saint-Paul, and the Rosary Chapel in Vence, decorated by Matisse. The kitchen was the main room in the Childs’ home. James Beard improvised a tomato and chard soup, and Julia Child prepared a copious Christmas dinner with two geese stuffed with pork sausage, chestnuts, and prunes, a ham in parsleyed aspic, and a bûche de Noël! Meanwhile, Paul Child concocted an aperitif cocktail with Dubonnet, vermouth, orange essence, and amber rum.

Behind this warm, welcoming atmosphere, a “seismic shift” was brewing, according to Luke Barr. “This was the moment these American food icons, who all fell in love with cooking in France and grew up revering French cuisine, decided to move away from it, at least a little.” Julia Child was tired of her role in her cooking show The French Chef. She wanted to try her hand at other dishes and explore different cuisines. M.F.K. Fisher had always dreamed of retiring to the South of France, having spent many happy years there in her life, but decided to move to California. Meanwhile, James Beard set about writing a book on regional American cuisine.

“They realized that French haute cuisine was not the only way and that there could be a great American cuisine,” says Luke Barr. In short, it was a declaration of independence. In August 1971, Alice Waters opened her restaurant Chez Panisse in Berkeley, a pioneer of the farm-to-table movement. Two years later, James Beard published Beard on Bread, the book that taught a whole generation how to cook authentic French bread at home. In the words of Luke Barr, “They may not have changed the world, but they changed the way we eat today!”

Provence, 1970 by Luke Barr, Clarkson Potter, 2014. 320 pages, 16 dollars.

Article published in the December 2020 issue of France-Amérique. Subscribe to the magazine.